TOPIC 8: Physical Assessment I

Introduction:

Physical assessment provides another perspective. Whereas the health history allows you to see your patient subjectively through hers or his eyes, the physical examination now allows you to see your patient objectively through your senses. The objective data complete the patient’s health picture. You will need all of the skills of assessment—cognitive, psychomotor, interpersonal, affective, and ethical/legal—to perform an accurate, thorough physical assessment. You also need to know normal findings before you can begin to distinguish abnormal ones. The best way to perfect your physical assessment skills is through practice.

Topic Learning Outcome (TLOs):

By the end of this topic, you should be able to:

- Discuss purpose of physical assessment.

- Differentiate complete from focused physical assessment.

- Identify tools used during the physical examination.

- Demonstrate physical assessment techniques.

Purpose of the Physical Assessment

Like the health history, the goal of physical assessment is not only to identify actual or potential health problems but also to discover your patient’s strengths. Data from the physical assessment can be used to validate the health history. For example, you can use the physical examination to assess clues you obtained from the history. Combined with the history data, your physical assessment findings are essential in formulating nursing diagnoses and developing a plan of care for your patient.

Types of Physical Assessment Components

Also like the health history, physical assessment may be either complete or focused. A complete physical assessment includes a general survey; vital sign measurements; assessment of height and weight; and physical examination of all structures, organs, and body systems. Perform it when you are examining a patient for the first time and need to establish a baseline.

On the other hand, a focused physical assessment zero in on the acute problem. You assess only the parts of the body that relate to that problem. It is usually performed when your patient’s condition is unstable, as a follow-up to a complete assessment, or when you are pressed for time.

Complete Physical Assessment

The complete physical examination begins with a general survey. A general survey includes your initial observations of the patient’s general appearance and behaviour, vital signs, and anthropometric measurements. Vital signs include temperature, pulse, respirations, blood pressure, and pulse oximetry, if available. Anthropometric measurements include height and weight.

Next, perform a head-to-toe systematic physical assessment. As you proceed from one area to another, remember that all systems are related, so a problem in one area eventually will affect or be affected by every other system. Therefore, look for the relationships between the systems as you proceed. For example, a skin lesion or a sore that is not healing may be the first sign of an underlying vascular problem or endocrine problem such as diabetes.

This assessment can be performed at any level of healthcare prevention—primary, secondary, or tertiary. In a primary setting, a complete physical examination is often performed to establish or monitor health status. For example, it may be required for school, camp, or a job. In an acute-care setting, a complete physical examination is often performed shortly after admission to establish a baseline and detect any other actual or potential problems. In a long-term–care setting, a complete physical examination is also helpful in establishing a baseline from which the patient’s condition can then be monitored and evaluated.

Because a complete physical assessment takes from 30 minutes to an hour, save time by asking some of the history questions (especially the review of systems) as you perform parts of the physical examination. Perform the assessment as soon as possible because the findings help to establish a baseline.

Focused Physical Assessment

The focused physical assessment consists of a general survey, vital sign measurements, and assessment of the specific area or system of concern. It also includes a quick head-to-toe scan of the patient, checking for changes in every system as they relate to the problem at hand. This scan may reveal associated problems and help you determine the severity of the problem. For example, if your patient is having breathing problems, do not limit your focused assessment to the respiratory system alone, because detecting confusion or cyanotic skin color changes may reflect severe hypoxia. The extent of the head-to-toe and focused examinations will depend on your patient’s condition and your findings.

A focused physical examination is indicated when your patient’s condition is unstable, when time constraints exist, or for episodic follow-up visits. In the last case, you have already performed a complete physical examination, and so now you perform focused physical assessments to monitor or evaluate your patient’s health status.

Focused physical assessments also can be performed at any level of healthcare prevention. In a primary setting, they may be used to monitor your patient’s health status, for example, performing a breast examination and teaching breast self-examination. In a secondary setting, after you have performed the initial physical assessment, focused assessments are often used to monitor and evaluate your patient’s health problem. For example, you might take vital signs and then auscultate the lungs of a patient who was admitted with pneumonia. In a long-term–care setting, a focused assessment is often used to monitor and evaluate your patient’s progress. For instance, if your patient is recovering from a total hip replacement, you will probably assess his or her musculoskeletal system, including gait, muscle strength, and prescribed range of motion (ROM) of joints.

Tools of Physical Assessment

The most important tools that you have for physical assessment are your senses. You will use your eyes to inspect, looking for both physical changes and nonverbal clues from your patient. You will use your ears to listen, hearing both sounds produced by various body structures and also what your patient is saying. You will use your nose to detect any unusual odors that may indicate an underlying problem.

You will use your hands to feel for physical changes and also to convey a sense of caring to your patient. You will also use a variety of equipment to perform the physical assessment and enhance your assessment abilities. As with any equipment, assessment equipment, especially equipment that is used for measurement, needs to be periodically checked and calibrated for accuracy.

Techniques of Physical Assessment

The four techniques of physical assessment are inspection, palpation, percussion, and auscultation. They are performed in this order, with the exception of the abdominal assessment. In this case, auscultation precedes palpation and percussion so as not to alter the bowel sounds.

Inspection

Inspection is the most frequently used assessment technique, but its value is often overlooked. With inspection, you use not only your sense of sight but also your senses of hearing and smell to inspect your patient critically. Do not rush the process; take your time and really look at your patient. Perform inspection at every encounter with your patient.

Inspection

Palpation

During palpation, you are using your sense of touch to collect data. Palpation is used to assess every system. It usually follows inspection, but both techniques are often performed simultaneously. Palpation allows you to assess surface characteristics, such as texture, consistency, and temperature, and allows you to assess for masses, organs, pulsations, muscle rigidity, and chest excursion. It also lets you differentiate areas of tenderness from areas of pain.

Types of Palpation

Two types of palpation may be performed—light and deep. Always begin with light palpation, if for no other reason than to put your patient at ease and convey a message of caring. Light palpation is applying very gentle pressure with the tips and pads of your fingers to a body area and then gently moving them over the area, pressing about 1⁄2 inch. Light palpation is best for assessing surface characteristics, such as temperature, texture, mobility, shape, and size. It is also useful in assessing pulses, areas of edema, and areas of tenderness. Closing your eyes while palpating may help you concentrate better on what you are feeling.

Deep palpation is applying harder pressure with your fingertips or pads over an area to a depth greater than 1⁄2 inch. Deep palpation can be single-handed or bimanual. When using the bimanual technique, feel with your dominant hand. You can place your other hand on top to help control your movements or to stabilize an organ with one hand while you palpate it with the other.

Palpating temperature changes with dorsal part of hand.

Palpating vibratory sensations and tactile fremitus with balls of hands.

Palpating with fingertips to assess pulsations.

Deep palpation, single hand.

Deep palpation, bimanual.

Palpating hands using patient’s hands.

Percussion

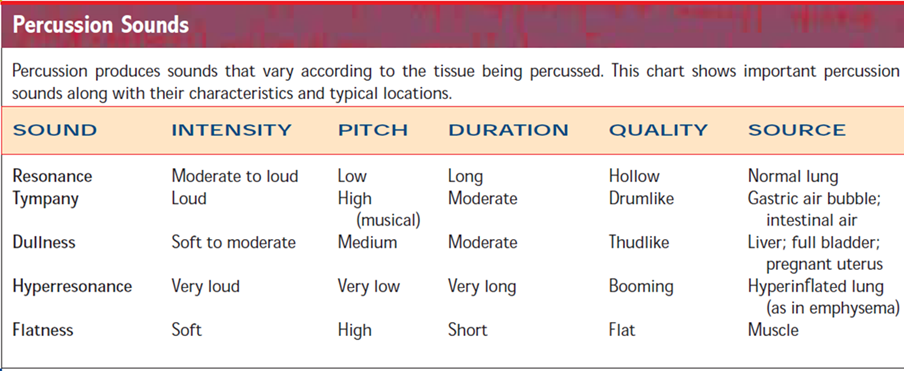

Percussion is used to assess density of underlying structures, areas of tenderness, and deep tendon reflexes (DTRs). It entails striking a body surface with quick, light blows and eliciting vibrations and sounds. The sound determines the density of the underlying tissue and whether it is solid tissue or filled with air or fluid. By determining the density, you can also “outline” the underlying structure, allowing you to determine the size and shape of the underlying structure.

Two factors influence the sound produced during percussion—the thickness of the surface being percussed and your technique. The more tissue you have to percuss through, the duller the sound. Percussion is a skill that usually requires practice to perfect. You also need to develop skill at identifying and differentiating the percussion sounds.

Direct percussion

Indirect percussion

Percussing for costovertebral angle tenderness.

Using a percussion hammer.

Auscultation

Auscultation involves using your sense of hearing to collect data. You will listen to sounds produced by the body, such as heart sounds, lung sounds, bowel sounds, and vascular

sounds. Auscultation can be both direct and indirect. Direct auscultation is listening for sounds without a stethoscope, but only a few sounds can be heard this way. Two examples are respiratory congestion in a patient who requires suctioning and the loud audible murmur of mitral valve replacement. For most of the sounds produced by the body, you will need to perform indirect auscultation with a stethoscope. Your ability to hear is affected by the quality of the stethoscope. The stethoscope should have the ability to detect both high- and low-pitched sounds.

Auscultation is also a skill that requires practice. You need to know what constitutes normal sounds before you can begin to identify abnormal sounds. Listen for the characteristics

of sound—the pitch, intensity, duration, and quality. Pitch may be high, medium, or low. Ask yourself, “Which part of the stethoscope was I using when I heard the sound best?” Intensity can range from soft to loud or can be graded on a scale. Ask yourself, “Could I hear the sound easily, or did I have to listen closely?” Duration may be short or long. Ask yourself, “How long was the sound?” Quality describes the sound. Ask yourself, “What did it sound like? Was it harsh, blowing, etc.?”

Listening with diaphragm of stethoscope.

Listening with bell of stethoscope.

You can watch the video clip on the FOUR techniques of physical assessment: "Inspection Palpation Percussion Auscultation for Nursing"

During the examination, you will use all four techniques of physical assessment: inspection, palpation, percussion, and auscultation. If your patient has identified an area of concern, begin there; otherwise, proceed from head to toe. Usually, the more private areas of the examination, such as the pelvic and rectal examination, are performed last. Do not rush. Pay attention to your patient’s responses, both verbal and nonverbal, and respond accordingly. For example, if you see that your patient is tiring, you may need to provide a short rest period. If you have identified any health teaching needs, the physical examination is an ideal opportunity for health teaching.