TOPIC 9: Physical Assessment II

Introduction:

Positioning and effective communication skills are essential to establishing the trust needed to proceed with the examination. You need to remember your ethical and professional responsibility to your patient in respecting his or her right to privacy and confidentiality.

Topic Learning Outcome (TLOs):

By the end of this topic, you should be able to:

1. Describes the positions needed for physical assessment

2. Define components of physical assessment

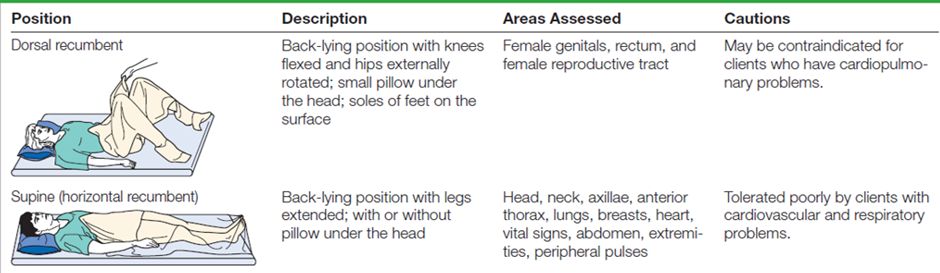

Positions for Physical Assessment

In order to perform a thorough physical assessment, you must ask the patient to assume various positions. Several positions are frequently required during the physical assessment. It is important to consider the client’s ability to assume a position. The client’s physical condition, energy level, and age should also be taken into consideration. Some positions are embarrassing and uncomfortable and therefore should not be maintained for long. The assessment is organized so that several body areas can be assessed in one position, thus minimizing the number of position changes needed. The table Examination Positions describes the positions needed to assess each area.

Components of the Physical Assessment

Before you focus on a particular system or area, perform a general survey and measure vital signs, height, and weight. During the health history, you performed a review of systems

to detect possible problems in other systems. This provided you with a subjective look at the relationship of these systems. Now take an objective look at each system as it affects each other before you focus on a specific system or area.

General Survey

Always begin the physical assessment with the general survey. This “first impression” of your patient begins as soon as you meet him or her. Use your senses and your observational skills to look, listen, and take note of any unusual odors. First, look for the obvious: apparent age, gender, and race. Then look closer for clues that might signal a problem. Also consider your patient’s developmental stage and cultural background; these may influence your findings and interpretation. Make a mental note of any clues detected on the general survey that you may need to follow up during the physical examination. When looking for clues, watch for signs of distress and check facial characteristics, body size and type, posture, movements, speech, grooming, dress, and hygiene.

Signs of Distress

Ask yourself, “Are there any obvious signs of distress (e.g., breathing problems)?” If signs of acute distress are apparent, do a focused physical assessment and address the acute problem.

FORUM: What other signs would indicate acute distress?

Facial Characteristics

Ask yourself, “What is the patient’s face telling me?” Do you see pain, fear, or anxiety? Does the patient maintain eye contact? Is her or his facial expression happy or sad? Facial expression may signal an underlying problem, such as masklike expression in Parkinson’s disease. Look at the patient’s facial features. Are they symmetrical? Ptosis of the eyelid may indicate a neurological problem; drooping on one side of the face may indicate a transient ischemic attack (TIA) or stroke; and exophthalmos suggests hyperthyroidism. Also look at the condition of your patient’s skin. It may reflect your patient’s age, but excessive wrinkling

from excessive sun exposure or illness may make the patient appear older than her or his stated age.

Body Type, Posture, and Gait

View your patient’s body size and build with respect to his or her age and gender. Is he or she stocky, slender, or of average build? Obese or cachectic? Proportional? Does your patient have abnormal fat distribution, such as the truncal obesity and buffalo hump seen with Cushing’s syndrome? Greet your patient with a handshake. The handshake will convey that you care but also allow you to assess muscle strength, hydration, skin temperature, and texture. Then take a close look at your patient’s hands. Do you see clubbing, edema, or deformities? Clubbing and edema may reflect a cardiopulmonary problem; deformities may reflect arthritic changes.

Watch how your patient enters the room. Are her or his movements smooth and coordinated, or does she or he have an obvious gait problem? Does she or he walk with an assistive device such as a cane or walker? Do you see a wide base of support with short stride length? Gait problems may suggest a musculoskeletal or neurological problem. Spastic movements or unsteady gaits may be seen in patients with cerebral palsy or multiple sclerosis. A shuffling gait is seen with Parkinson’s disease. Patients with a wide base of support and short stride length may have a balance or cerebellar problem.

If your patient is bedridden, observe his or her ability to move from side to side, sit up in bed, and change positions. Determine how much assistance he or she needs with moving. Any problem detected during the general survey should be further evaluated during the physical examination.

The patient’s posture may also reveal clues about her or his overall health status. Is she or he sitting upright or slumped? Can she or he assume a supine position? Is there a position that she or he prefers? A slumped position may indicate fatigue or depression. Patients with cardiopulmonary disease often cannot assume a supine position. They prefer a sitting or tripod position because it eases breathing. Patients with abdominal pain also may find it difficult to assume a supine position. Sitting hunched over or in a side-lying position with legs flexed often eases the pain.

Speech

Listen to your patient’s speech pattern and pace. Speech reflects the mental state, thought process, and affect. Are your patient’s responses appropriate? Speech patterns and appropriateness of responses reflect his or her thought process. Pressured speech, inappropriate responses, and illogical or incoherent speech may be associated with psychiatric disorders. Pressured, hurried speech may also be seen in patients with hyperthyroidism. Note the tone and quality of his or her voice. Do you hear anger? Sadness?

Changes in voice quality may indicate a neurological problem, specifically, a problem with cranial nerve (CN) IX (glossopharyngeal) or CN X (vagus). Notice whether his or her speech is clear or garbled.Aphasia can be expressive (motor/Broca’s), receptive (sensory/Wernicke’s), or global, a combination of these. Aphasia of any type is often associated with a TIA or stroke.

The patient’s vocabulary and sentence structure offer clues to her or his educational level, which you will need to consider when developing teaching plans. Also, be alert for foreign accents. You need to determine if there is a language barrier and solicit an interpreter, if needed.

Dress, Grooming, and Hygiene

The way your patient is dressed and groomed tells a great deal about his or her physical and psychological wellbeing. Is he or she neatly dressed and well-groomed or is he or she untidy? Disinterest in appearance may reflect depression or low self-esteem. Poor hygiene and a untidy appearance may also reflect the patient’s inability to care for himself or herself.

Also take note of the appropriateness of dress for the season and situation. Inappropriate dress may be a sign of hyperthyroidism, which causes heat intolerance. Worn clothing may indicate financial problems. Be sure to take note of any unusual odors, such as alcohol or urine, that may indicate a problem and warrant further investigation.

Mental State

Determine if your patient is awake, alert, and oriented to time, place, and person. Are her or his responses appropriate? Bizarre responses suggest a psychiatric problem. Is your patient lethargic? Many conditions can affect the level of consciousness. Determine if this is a change in your patient’s mental status. If so, investigate further. Also take note of your patient’s medications, because they may be contributing to the change in mental status.

Cultural Considerations

Note any cultural influences that may affect your patient’s physical characteristics, response to pain, dress, grooming, and hygiene. Patterns of verbal and nonverbal communication may also be culturally influenced. Keeping these factors in mind will help you avoid making hasty, inaccurate interpretations. Here are a few examples of cultural differences:

■ Asian Americans are often shorter than Westerners.

■ European Americans and African Americans tend to speak loudly, whereas Chinese Americans speak softly.

■ Asians may avoid eye contact with anyone considered a superior.

■ Japanese and Korean individuals maintain a tense posture to convey confidence and competence, whereas Americans assume a relaxed posture to convey the same message.

Developmental Considerations

Consider the developmental stage of your patient. Here are some points to keep in mind when performing the general survey:

Children

■ Behavior should correspond with the child’s developmental level.

■ Children tend to regress when ill.

■ Take note of the relationship between child and parent.

Pregnant Patients

■ General appearance should reflect gestational age.

■ Look for normal changes that occur with pregnancy, such as wide base of support and lordosis.

■ Look for swelling.

■ Note patient’s affect and response to pregnancy.

Older Adults

■ Look for normal changes that occur with aging.

■ Look for clues of decreasing ability to function, especially dress and grooming problems.

■ Pay attention to your patient’s affect, especially signs of depression.

■ Note changes in mental status such as confusion, and then consider medications, hydration, and nutritional status or an underlying infection as a possible cause.

Documenting the General Survey

Documentation of the general survey records your first overall impression of your patient. It should include age (actual and apparent), gender, race, level of consciousness, dress, posture, speech, affect, and any obvious abnormalities or signs of distress. Here is an example of documentation:

Mr. Bato, 56-year-old Malaysian-Indian male, looks younger than stated age; alert and oriented to time, place, and person. Neatly dressed, well groomed. Well-developed physic. Speech clear, responds appropriately, affect pleasant. No signs of acute distress.

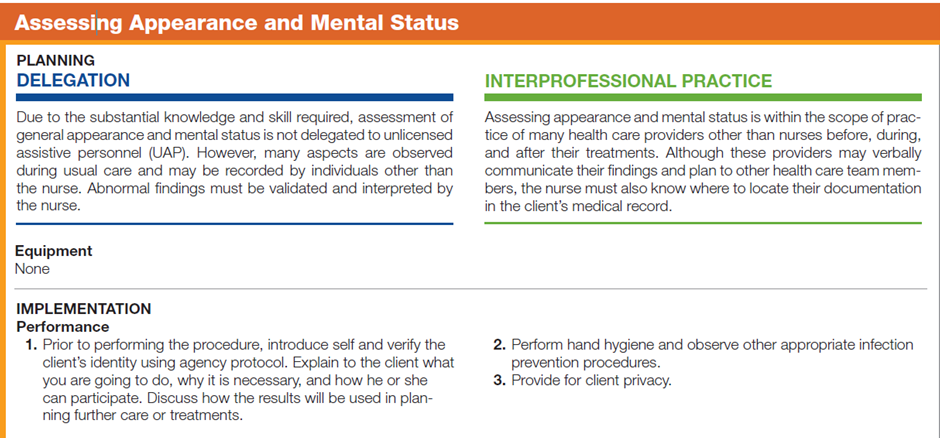

The following is the Step in Assessing Appearance and Mental Status of a patient:

For better understanding, you may watch the video clip on “General Survey and Vital Signs"

Video:

Vital Signs

Vital signs include measurements of temperature, pulse, respirations, and blood pressure. They are the most frequent assessments performed, reflecting cardiopulmonary function and the overall functioning of the body.

The purpose of taking vital signs is to:

■ Establish a baseline.

■ Monitor the patient’s condition.

■ Evaluate the patient’s response to treatments.

■ Identify problems.

Documenting Vital Signs

Vital signs are often documented on graphic charts, which allow you to monitor or plot the patterns of the vital signs. This is very helpful in evaluating the effectiveness of treatment. Vital signs may also be documented in narrative form. For example: T 36.8° C; P 88 bpm, regular; R 16 per min, unlaboured, regular and deep; BP 120/80mmHg, lying,118/80mmHg, sitting, and 118/80mmHg standing.

Height and Weight

Anthropometric measurements provide valuable data about your patient’s growth and development, nutritional status, and overall general health. Be sure to document the measurements in centimetres or inches, kilograms or pounds. Because children have frequent changes in growth and development, their measurements are often documented on growth charts for easy monitoring.

Head-to-Toe Scan

Whether you are doing a complete or a focused physical assessment, remember that all body systems are interrelated. A problem in one system will eventually affect or be affected by every other system. When performing a complete physical assessment, perform a thorough assessment of each system, looking for relationships. When you perform a focused physical assessment, an in-depth assessment of one system begin by scanning the other systems, looking for changes as they relate to the system being assessed.

For example, suppose you were performing a focused assessment of the cardiovascular system. Here are some of the affects you should look for:

■ Integumentary: Look for color changes, pallor, edema, and changes in skin and hair texture and growth. Patients with cardiovascular problems may have edema and thin, shiny, hairless skin.

■ Head, eyes, ears, nose, and throat (HEENT): Look for periorbital edema. Funduscopic examination may

reveal vascular changes.

■ Respiratory: Look for cyanosis and breathing difficulty. Auscultate for adventitious sounds such as crackles

that are associated with congestive heart failure (CHF).

■ Breast: Assess for male breast enlargement that may occur with cardiac medications such as digoxin.

■ Abdominal: Assess for ascites and hepatomegaly, which may be associated with CHF.

■ Musculoskeletal: Assess for muscle weakness and atrophy associated with disuse.

■ Neurological: Assess level of consciousness. Confusion, fatigue, and lethargy may be associated with decreased CO and hypoxia.

Documenting Your Physical Assessment Findings

Once you have completed the physical assessment, document your findings. Because writing should be kept to a minimum during the examination, document your findings as soon as possible, while they are foremost in your mind. Document accurately, objectively, and concisely. Avoid general terms such as “normal. “Record your findings system by system, being sure to chart pertinent negative findings. Once you have completed your objective database, combine it with your subjective database, cluster your data, identify pertinent nursing diagnoses, and develop a plan of care for your patient.